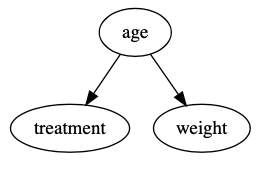

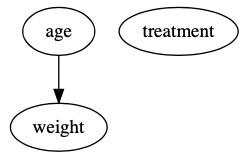

A PhD student collects some data about patients’ weight from a hospital database. Some of the patients were given an experimental drug, and the rest were not given any medication. The student wants to know whether the experimental drug has a causal effect on patients’ weight, however, how the hospital determined which patients received the drug is unknown. In this example, confounding is going to be a serious concern because there are likely factors that influenced both the treatment assignment and patients’ weight. Check out the hypothetical DAG (directed acyclic graph) below:

This DAG says age is a common cause of both treatment assignment and weight; therefore, it needs to be properly handled to estimate the causal effect of the treatment on an individual’s weight. Check out our previous post that walks through confounding and DAGs if this sounds unfamiliar. What should the PhD student do? One technique that works well in a scenario like this is propensity score matching. Let’s break that down into two parts, and then we’ll walk through an example.

Matching

I think about matching as two distinct steps. First, we separate our data into treated subjects and untreated subjects. In our example, this would be patients who received the experimental drug and patients who did not receive the drug. Second, for each treated subject, we find at least one untreated subject that is similar to the treated subject. If we cannot find a similar untreated subject for a given treated subject, we remove the treated subject from our analysis. Untreated subjects that don’t get matched to treated subjects also get removed. When we’re done, we estimate any causal effects using only the treated subjects and their matches.

This new population of matched pairs will be similar enough that confounders are no longer a threat to our estimates. To drive this point home, think about the following: if all subjects are 50 years old, age can’t possibly be a confounder. We don’t necessarily need similarity this extreme, but the closer we can get, the more accurate our estimates of the causal effect will be.

We use propensity scores to determine if two subjects are similar during the matching process.

Propensity Scores

I think of a propensity score as a probability a subject was treated given a set of confounders. This probability can be estimated using a logistic regression model, although there are more robust techniques1 . We say two subjects are similar if the difference between their propensity scores is below some threshold. This threshold generally depends on your sample size; in an ideal world with infinite data, we would only use exact matches. I think a good rule of thumb is to have the smallest threshold possible without creating a dubious sample size (e.g., 10 subjects).

Matching is only one way we can use propensity scores. There are other techniques, such as stratification, which have their own pros and cons.

Example

The best way to understand how propensity score matching works is to see it in action. First, we’ll create some fake age data:

age = stats.norm.rvs(loc = 50, scale = 10, size = 1_000)

The code above will generate a distribution of ages which is concentrated around 50, and mostly falls between 20 and 80. Next, we’ll create some treatment data that depends on age. We’ll add some randomness here because a standard logistic regression model will struggle if age is a perfect predictor of the treatment variable:

drug = (age > (50 + stats.norm.rvs(loc = 0, scale = 5, size = 1_000)

This code will only assign treatment to older people, but with some randomness, might assign treatment to people younger than 50. Finally, we’ll create some fake weight data that only depends on age:

weight = 75 + age*2

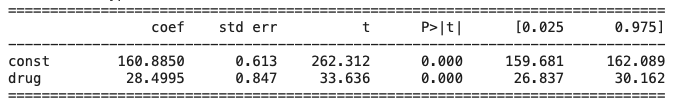

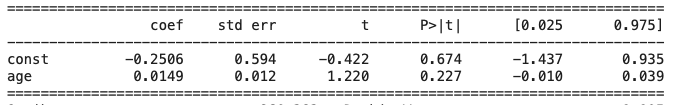

The data we created matches the hypothetical DAG we introduced above. Let’s see what happens if we naively run a linear regression to estimate the causal effect of the experimental drug on weight, without worrying about age:

We would estimate a significant and positive causal effect of the experimental drug on weight, even though none exists in the data! Let’s see how propensity score matching can eliminate this bias.

Estimating Propensity Scores

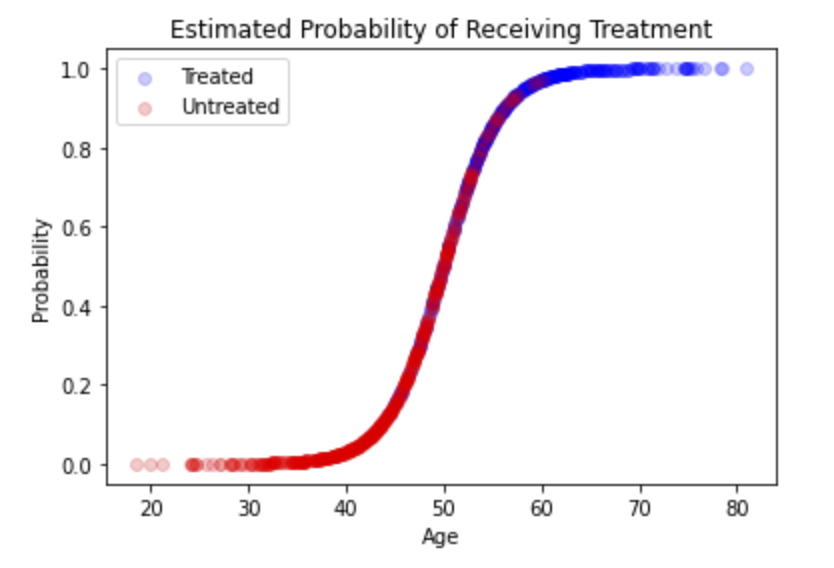

The first step is to estimate the probability each individual is treated using a logistic regression model (i.e., propensity scores). Here, we’ll include the confounder we are worried about, age, as a predictor in the model. The propensity score for each individual will represent the probability that individual receives treatment given their age. These probabilities are plotted below:

That’s all we need; we have our propensity scores.

Matching - Creating a New Population

Visually, you can think of matching as taking the section of the population with overlapping propensity scores, which is the overlapping red and blue dots in the figure above. We are restricting our analysis to the section of the population in which age is not a confounder (i.e., subjects in the treated and untreated groups are similar enough that they can’t be classified by their age). There is nothing fancy here; the logic can be implemented in an iterative loop:

- For each treated subject, find every untreated subject with a propensity score within some threshold (e.g., 0.0003).

- If there is at least one match, add the treated subject and all matches to the new population.

- If there are no matches, do not add the treated subject to the new population.

- Remove all duplicates from the new population.

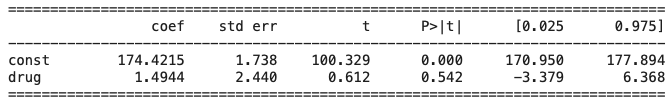

For the sake of this example, we’ll use a threshold of 0.0003. Let’s see what happens when we re-run the original linear regression model, but only using the data for our matched population:

The confounding is gone and we no longer estimate a significant causal effect of the experimental drug on weight! Here, we use a p-value cutoff of 0.05 to classify significant estimates.

Explanation

How did that work? In our new population of matched pairs, age does not have a causal effect on treatment because we only included subjects with similar probabilities of being treated given their age. Age is no longer a significant predictor of treatment in the new population and is no longer a confounder. The DAG for our new population looks like this:

We can see evidence of this by running a linear regression model to estimate the causal effect of age on weight in the new population:

There is none! That’s the magic of propensity score matching. This independence in our new population is sometimes called marginal exchangeability2.

Interpretation

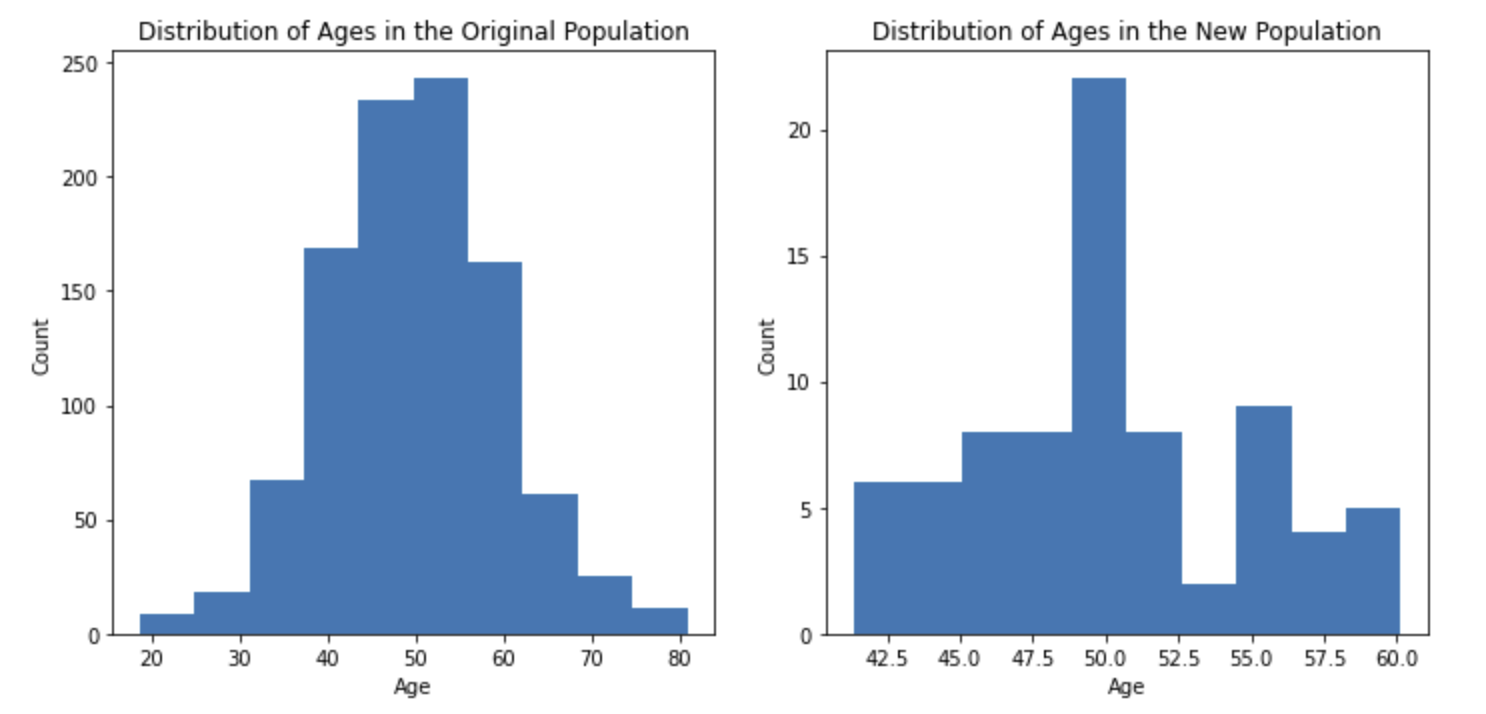

It is important to understand how to interpret effects estimated after applying propensity score matching. The estimated causal effect is only true for the new population of matched pairs, which often has different characteristics than the original population. For instance, let’s look at the age distributions of our original and new populations:

Our matching process removed all subjects below the age of 40 and above the age of 60. Although our original population included subjects between the ages of 20 and 80, our conclusions would only pertain to people between ages 40 and 60. In general, new populations of matched pairs will have many differences (e.g., age, height, weight, race) and it is important these differences are included in reported conclusions. If the characteristics of the population didn’t change, there would have been little need for matching in the first place.

In our example, we matched untreated subjects to treated subjects. This created a new population similar to the treated population. We could have also matched treated subjects to untreated subjects, which would create a new population similar to the untreated population. This is an important distinction because, in general, the treated and untreated populations will be different. If, for instance, treated people tend to be taller and untreated people tend to be heavier, the population for which your conclusion holds will differ depending on which direction you match. This decision typically depends on the purpose of your research project.

In short, propensity score matching typically yields conclusions that only hold for a subset of your original population. Extending your findings to other populations is known as external validity or portability

Tradeoffs

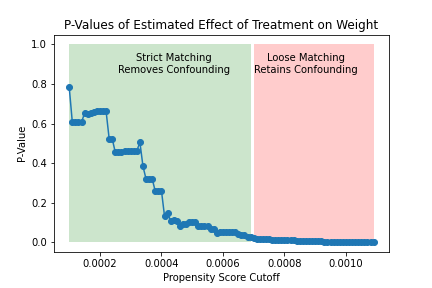

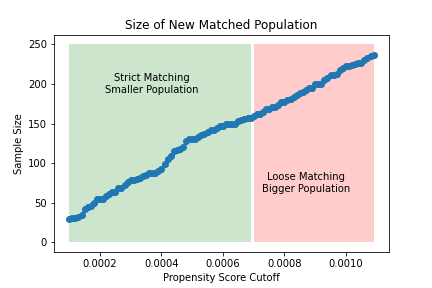

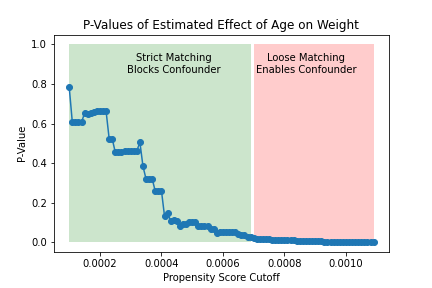

The threshold of 0.0003 we used in our example was arbitrary. We could have used 0.00035 or 0.00047. This is a good place for sensitivity analysis (e.g., if your results only hold for one threshold, they aren’t that convincing) but we can also use it to better understand how propensity score matching works under the hood. Let’s repeat our example analysis with 100 different threshold values and see how our results change:

The figure on the left shows how the significance of the estimated effect of the treatment changes as the matching threshold increases. For lower thresholds (i.e., stricter matching), the treated and untreated are sufficiently similar and we estimate an insigificant causal effect of the treatment. For higher thresholds (i.e., looser matching), the treated and untreated are not similar enough to eliminate confounding, and we estimate a significant causal effect of the treatment. This can also be seen in the figure on the right, which shows that strict matching eliminates the causal effect of age on weight (i.e., confounding) while looser matching fails to do so.

The figure in the middle highlights the tradeoff we make by lowering the matching threshold. Stricter matching is more likely to eliminate confounding at the price of a smaller sample size.

Summary

Propensity score matching is one technique that can be used to combat confounding and is easily broken down into three steps3:

- Run a logistic regression model to estimate the probability each subject receives treatment given a set of confounders.

- Divide your subjects into treated and untreated groups, and use propensity scores to created a new population of matched pairs.

- Conduct any further analysis only using data from the new population.

This method works by creating a subset of the original population in which the treated and untreated subjects are sufficiently similar across all confounders. There are two important considerations when applying propensity score matching and interpreting the results:

- The sample size of your new population of matched pairs.

- The demographics of your new population and how they differ from your original data.

Note: All source code written for this post is available in a Python notebook here: https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1e1vWFQEWOUntb81Uj1syKscdBQIT9HhC?usp=sharing

1: An excellent resource which covers more ways to use propensity scores and alternatives to logistic regression: https://www.rand.org/pubs/presentations/PT147.html↩

2: Check out this book for a ground-up explanation of marginal exchangeability and all things related to causal inference: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/miguel-hernan/causal-inference-book/↩

3:. An additional resource for understanding and applying propensity score matching: https://sites.google.com/site/econometricsacademy/econometrics-models/propensity-score-matching↩